The Rectangle Class is Wrong

Many tutorials on object-oriented programming use geometric shapes because they think it’s an easy way to start. It could be an easy way to start, but most people make it hard because they don’t think about what a shape actually is, what they want it to do, or how it should relate to other objects.

- Object-Oriented Coding in Python

- Object-oriented Rectangle program

- A Solution to the Square-Rectangle Problem Within the Framework of Object Morphology

Let’s start with something simple. We’ll do regular, closed, convex polygons, which is cheating a bit but a decent place to start. What is a polygon, what makes it regular, and what does it know about itself? As an aside, consider that this is fully in the realm of philosophy, and that in general I think people going through formal Computer Science training have a huge blind spot here. Accidental programmers coming up through the sciences (like me) and humanities have a completely different way of approaching their evaluation and categorization of knowledge.

At its most basic level, meaning that we can’t know anything less or more fundamental, a closed, regular, convex polygon has a number of vertices and none of its edges cross each other. The number of sides and angles are completely determined by that one number. We’ll question that assumption later, but for now let it stand.

Once we know that, we don’t need to know anything else. Some people will object to say that we need to know a length of a side, but that’s not something the polygon knows about itself. That’s something we impose on the polygon when we choose a particular measure. Consider, for example, a polygon with a side length of 1 inch, or 2.54 centimeters, or 0.1 bananas. The number doesn’t particularly matter.

There’s a physics joke: what’s the speed of light in a vacuum? It’s 1 (in units of the speed of light).

Which of those measures is something intrinsic to the polygon that changes its form? None of them. The relative length of the sides, the number or vertices, and the number of sides are unaffected by our ruler.

class ClosedRegularConvexPolygon

def initialize( sides ); @sides = sides; end

def sides; @sides; end

end

square = ClosedRegularConvexPolygon.new(4);

puts square.sides;I’m going to omit all error and sanity checking since that’s just a matter of programming that obscures the structure. Not only that, error checking and handling are often an architectural issues about the interplay of objects, so there’s no True Way to do it. Assume that the methods do whatever they need to do to ensure their arguments make sense, and complain in an appropriate way when they do not. For example, ClosedRegularConvexPolygon needs at least three sides.

If we only ever had to deal with closed, regular, convex polygons, we are done. There’s no reason to go any further, especially if there are better things to do. Sometimes, that’s enough for the application. And here’s a big point to remember to as you read through the rest of this: Our goal is not to model the Platonic ideals of the world. Instead, we want to get to a suitable level of abstraction that allows us to easily work with and maintain code so that we don’t have problems later. If our design is good, we won’t have to work around it later. Not only that, we can hide various sins behind methods and classes. We all know that the Real World forces inconvenient constraints on otherwise tidy solutions. We deal with that as best we can without making more work for us or others.

But, notice what’s missing in the our class. We don’t give this thing a name. It’s not a square, or a rectangle, or whatever. And, we have no way to adjust anything.

This is the first (and second) place where most examples start to paint themselves into corners. Once we have a polygon, why would we ever want to change it?

That’s not as stupid as it sounds. Not all object have to be mutable. If we want something different, we make a new object. Mutability is, by the way, one of the chief complaints that functional programming zealots bring up about OO. But, it’s not something that’s intrinsic to OO.

The goal of the misguided examples is to show inheritance, so it ignores the 15 other things that impact the problem. Conversely, every regular, closed, convex polygon of four sides (there’s on one!) can be the same object everywhere in the program. That is, you only need one square. Envision all sorts of objects, representing distinct things, that all have the same interface (polymorphism). In the short term, it seems like inheritance provides re-use because one class steals parts of the other class. But, if you choose the wrong general attributes, the specifics will be wrong too.

We don’t want to start adding methods to only some of them because that breaks polymorphism: every time we add a method to one class, we have to add it to every such class. Do those methods represent something fundamental about the object, and if they don’t, do they belong in the class? There are other ways to handle this.

In the abstract, our polygon doesn’t have a magnitude. That’s something done elsewhere. A graphics thingy may scale the polygon, but that’s not something the polygon knows about itself just like it doesn’t know it’s orientation. These things are projected onto a polygon by something else. They are external descriptions. Until there are concrete measures, we only have relative distances and relative areas. But, these are derived properties. That is, if we know what we already know, we can compute these. In good database design, we remove anything that we can compute from something else. Consider that for object designs too.

Likewise, the polygon doesn’t have a name. In English, a closed, regular, convex polygon with four sides is called a “square”, but in French it’s un carré. But maybe I want to call it MegaEquiQuad. That name is not a property of the polygon; it’s something that we project onto it based on our estimation and categorization. We choose some property that sets apart one thing from another, then assign a name to represent that distinction. The thing doesn’t care; it is what it is. We don’t need something else, like a class name or inheritance relationship, to define that. Deciding to have a name carves the projection into the code. We’ve limited the object based on an externality. If we can avoid that, don’t do it.

This brings us back to philosophy. What do we really know and what do we add to these ideas? What’s the simplest way to define and think about them so that we do less overall work?

Compare this to internationalization and localization where message text is merely a pointer into a dictionary. The message is just the message. Maybe it’s just message 1202. We don’t care what 1202 is or what the local languages are. Something else handles all that.

Non-regular polygons

Knowing the number of vertices is everything we need to have in the regular case, but it’s not the best we can do. We specify the number of vertices because we assume several things. Closed regular polygons all have the same angles at each vertex, there are at least three vertices, the sides are the same length, all angles are less than 180 degrees, and the sum of all exterior angles is 360 degrees. This is fundamental to a closed, regular, convex polygon.

#!/usr/local/bin/ruby

class ClosedPolygon

def initialize( angles ); @angles = angles; end

def sides; @angles; end

end

square = ClosedPolygon.new(4);

puts square.sides;There’s a problem. Now that we’ve left the realm of regular polygons, we can no longer assume anything about the relative length of the sides. Given an array of angles, we know the number of sides, but there are infinite numbers of polygons that have the same angles. Now we need to know something about their sides.

Are we getting a bit pedantic here? It may seem so, but this is a simple demonstration of the process you should go through when choosing objects for much more complex systems. What really defines that thing you are thinking about, and knowing that, what things does it know and what can it do?

An easy thing might be to specify two arrays: one for edge length and one for angles. Again, we skip the checks to ensure the array arguments are the same length and that the numbers can actually represent a closed polygon. For example, if there are four vertices, we can’t have three sides of length 1 and another of length 5 million. That’s not a closed polygon.

But, how would a Ruby programmer handle this? The sanity checking can’t be part of the instance because a polygon is already a polygon. There’s nothing it could do but say it is a polygon. So, we move that up to a class method.

Look what we have to do in initialize now. We already have a ClosedPolygon object! We don’t even know if we have something sane, but we are already in the wrong part of the code! That’s not a huge deal because we can easily extract ourselves before we return an instance to the caller, but it’s messy. Our design already has a problem. We should never have had an instance that had to reach back up to the class to stop what should have never happened.

#!/usr/local/bin/ruby

class ClosedPolygon

def self.sanity( lengths, angles ); ...; end

def initialize( lengths, angles );

raise "Nope" if ! self.class.sanity( lengths, angles );

@angles = angles;

@lengths = lengths;

end

def sides; @angles.length; end

end

square = ClosedPolygon.new( Array.new(4) { 1 }, Array.new(4) { 90 } );

puts square.sides;

pentagon = ClosedPolygon.new( Array.new(5) { 1 }, Array.new(5) { 72 } );

puts pentagon.sides;

house = ClosedPolygon.new(

[ 1, Math.sqrt(1/2), Math.sqrt(1/2), 1, 1 ],

[ 90, 45, 90, 45, 90 ]

);

puts house.sides;This isn’t an entirely trivial point. Consider the Single Responsibility Principle. Who’s job is it to check if this instance can be constructed? This is the point where, if you care enough, you diverge from what most Ruby programmers are willing to tolerate because this isn’t what the language wants you to do even as it allows it. You make your own new, which has to handle the new interface. This checks the arguments and only creates the instance if it makes it past that step:

class ClosedPolygon

def self.new( *arguments, &block )

raise "Nope" if ! self.sanity( *arguments )

super

end

def self.sanity( lengths, angles );

lengths.length == angles.length

end

def initialize( lengths, angles );

@angles = angles;

@lengths = lengths;

end

def sides; @angles.length; end

endSince that combination is not a closed polygon, so it will never a ClosedPolygon object. There’s never a chance for it to do ClosedPolygon things. We’re not going to the pet store to buy a dog, being sold a collar, and told that that’s a dog. A dog object doesn’t have to know it’s not a collar, nor an airplane, nor a prime number. It’s a collar and the only way it can be a collar is by being a collar. Ask Plato what a man is and watch Diogenes own him (and they were all about geometry as the purest expression of truth even after Pythagorus had to threaten people not to talk about the irrational length of the hypotenuse):

house = ClosedPolygon.new(

Array.new(10) { 1 },

[ 18, -72, Array.new(4) { [144, -72] } ].flatten

);What is that? Maybe this LOGO program will help (try it):

clearscreen

right 18 forward 100

left 72 forward 100

right 144 forward 100

left 72 forward 100

right 144 forward 100

left 72 forward 100

right 144 forward 100

left 72 forward 100

right 144 forward 100

left 72 forward 100

We’re very close to a much more general idea: A closed path. Our sanity checker did whatever it needed to do to ensure that no part of the path crossed itself, but do we really care? What if we just did this so that paths crossed, giving us a star polygon instead of a convex one:

clearscreen

right 18 forward 200

right 144 forward 200

right 144 forward 200

right 144 forward 200

right 144 forward 200

Now our sanity checker need only ensure that we end up back at the spot we started. But, we’re not going to do there. We know we can easily do that:

def ClosedPath

... stuff ...

endThis actually makes more sense if we are going to think about angles and lengths. A path isn’t a shape, at least in the way we normally think about it. But a path may be what we want. If we want to draw it on the screen, for instance, we need the path, not the shape. The shape is a consequence on the path.

And, we should be thinking about our requirement that the path be closed at all. There’s nothing in the object that demands it. However, we don’t want to reduce ad absurdium just because we can. We want to go as far as our problem needs along with a little cheat space for requirements we discover later.

Points instead of coordinates

I used angles and lengths as the properties, but that’s not the only way to define this. If I define coordinates, in some idealized space, I can get the angles and lengths from those. We might specify the polygon as the closed path connecting points. A square would be (0,0), (0,1), (1, 1), (1, 0). We could easily convert these to angles and lengths and answer the same questions as before.

Which should we choose? The problem will tell you. What information do you know and what’s the least amount of work you need to make it usable? What are you trying to do with it and what sort of questions are you trying to answer?

Later you’ll see some transformations. If you want to orient and scale the polygon in space, it’s probably easier to work in coordinates from the start.

Are you using the right property?

We started with regular convex polygons, where we only needed to know the number of vertices to define the object. Now we’ve moved on to defining angles and lengths. This changes the situation somewhat.

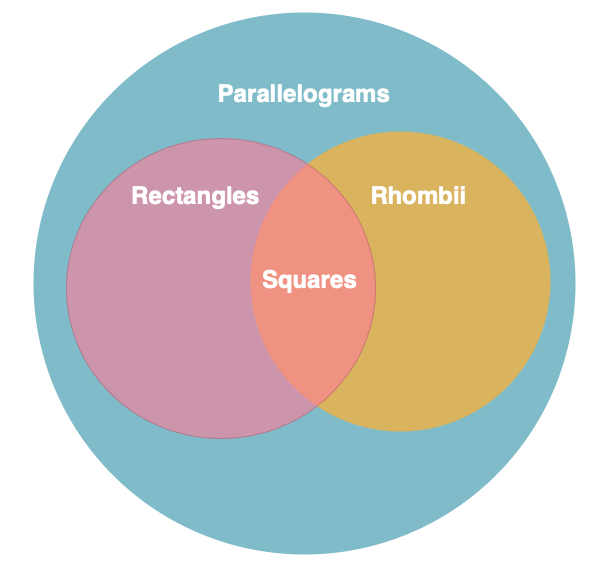

If we are thinking about angles and lengths, a square is more similar to a rhombus. Both have equal sides, and specifying exactly one angle determines everything else. But, where does a parallelogram fit into that? There are two more fundamental types, both of which may be useful in our application, and rectangles and squares are particular expressions of those.

Which set of ideas should you use when you want to inherit from something? A square and rectangle share some properties, and when we look closely enough, we see they are related in more fundamental ways, but as siblings, not parent nor child. We don’t need to know any of this though because we didn’t try to classify the polygons. We used their fundamental properties. We’ll see classifications in a moment.

This is where GUI examples of the same problem show up. If we have some widget in our, perhaps a window, what does its manifestation express? Often, examples show a widget inheriting from more than one thing because that sort of modeling expresses it as a frankenstein monster of ideas: scrollbars, menus, text pane, and so on.

Curves

Now imagine adding a circle. What defines a circle? It’s all the points equidistant from some point. Do we care what that center is? Not really. We could assign it some value, but it’s really a translation from some coordinate system we don’t know yet.

But, a circle is a degenerate case of an oval, which has two foci and a combined distance to them. We need to know how far apart the foci are from each other compared to that combined distance to define the ellipse.

Known polygons

We know how to construct any closed polygon that we like, but we don’t want to specify it minutely every time we need a shape. We can make special methods to construct what we need, and we don’t need inheritance to do this. We have a class that returns something (anything) that does what we want:

class ClosedRegularPolygon

def self.new( *arguments, &block )

sides = arguments[0]

ClosedPolygon.new(

Array.new(sides) { 1 },

Array.new(sides) { 360 / sides },

);

end

endSome people call this a “factory” and even insist that “factory” show up in the name. Or, maybe they call it “adapter”. But, we don’t care that it returns an instance of a different class. We don’t care how we got the instance; we have it and it works.

Go one step further:

class Square

def self.new( *arguments, &block )

ClosedRegularPolygon.new(4)

end

endAnswering questions

There are several things we may want to know about the polygon:

- sides

- vertices

- path

If we had been more general and implemented things as possibly open paths, we might also ask about that:

- open?

- closed?

These are questions that we’d have for any polygon, so we could add instance methods to ClosedPolygon to answer them. We don’t particular care how they answer them, so maybe they figure it out just in time and cache the result. Since the polygon will not change, the answers to these questions don’t change either.

Beyond that, we might want to categorize them, but this isn’t something the polygon cares about. It is what it is and it doesn’t care what box we want to put it in.

- regular?

- convex?

- star?

- square?

- rhombus?

- parallelogram?

And now here’s a big point. A polygon is not a square because we call it a square. It’s a square because it satisfies the external categorizations we apply. A parallelogram, rhombus, rectangle, and even other categories probably, can supply an exemplar that satisfy the definition of a square. How would any sort of inheritance faithfully represent those overlapping sets?

These are things that a categorizer can figure out based on the properties. It’s not a huge tragedy to add these to the polygon class itself, but we don’t want to pollute its list of methods with tens or hundreds of external judgments. Remember, if we are consistently adding methods to an instance to support something an actor wants to do with that instance, we’re probably doing it wrong.

class Categorizer

def self.closed?( polygon )

polygon.can( :angles ) and

polygon.can( :lengths ) and

1 # some complicated code to figure out the path

end

def self.rectangle?( polygon )

self.parallelogram?( polygon ) and

polygon.angles.uniq.size == 1

end

def self.regular?( polygon )

self.closed?( polygon ) and

polygon.angles.uniq.size == 1

end

def self.irregular?( polygon )

! self.regular?( polygon )

end

def self.rhombus?( polygon )

self.parallelogram?( polygon ) and

polygon.lengths.uniq.size == 1

end

def self.parallelogram?( polygon )

self.closed?( polygon ) and

polygon.angles.size == 4 and

( polygon.angles[0] == polygon.angles[2] ) and

polygon.lengths.uniq.size <= 2 and

polygon.angles.uniq.size <= 2

end

def self.square?( polygon )

self.rhombus?( polygon ) and

polygon.angles.uniq.size <= 1

end

end

if( Categorizer.square?( some_shape ) )

...

endThis way, the person interested in categorizing the shape can supply whatever judgments they want without having to change the other classes. When we consider the flexibility of this arrangement, moving all the questions into such a class makes more sense. We can easily change from looking at the number of sides to using some other property, and we can easily add more categories. For example, perhaps we want to know about kites, diamonds, or trapezoids.

We can make these changes to the categorizer without disturbing anything else. We’re future proofing here.

There is a challenge, here, though. Since the polygons are immutable, once we’ve asked the question, we know the answer forever. As presented, the code acts like it doesn’t know. We could give up some memory to cache answer, speeding up our program a bit, or we can save some memory but lose a little speed. That trade-off is not absolute: it’s different depending on the needs of the application. But, also consider this: since the answers are fixed, we wouldn’t want to calculate them in the polygon. The polygon just knows. Either we hard-code the answers or compute all the answers and cache them every time we create a new polygon. This leads to the idea that there would only ever be one instance of any particular polygon. No two polygon objects would ever be the same, because in that case we would have re-used the same object. But, that’s more work too.

There are things we can’t ask. For example, we don’t know where the vertices are in space because the polygon is an ideal one. It doesn’t exist in space yet. We’ll deal with that in a moment.

Placers, Scalers, and Rotaters

So far so good. This is all very simple. We have one class that does some real work and a few convenience classes that handle the details for us. We don’t know about any of this. We ask for a square and get something that knows about squares.

But we don’t want polygons floating around our program knowing about polygons. We want to do other things with them. These things that we want to do aren’t properties of the polygons. So, let’s place a polygon somewhere. I’m not going to fill this out because you get the idea:

class PlacedPolygon

def initialize( shape, origin, angle, scale )

@polygon = polygon

@origin = origin # some point object

@angle = angle

@scale = scale

end

def rotate( angle )

@angle += angle

end

def translate( x, y )

... change some point object ...

end

def scale( n )

@scale *= scale

end

endNow, when we want to render a polygon somewhere, we just walk its path, applying the various translations. The polygon doesn’t change because we rotate it. If I want to do things such as detect overlaps, we place two polygons and do whatever we need to do to check if their paths cross. But, an overlap is not a property of the polygon. Something else knows how to check that.

The polygon doesn’t even know how to walk its path. It doesn’t think about that at all because it’s just a polygon. It has an idealized path up to the point that we apply translation and scale to it. We will have to figure out how to start the path, and perhaps define a “north”, but that’s not necessarily something we need to figure out at the lowest level. It’s a particular thorny problem too. Do we assume that we start by point “north” then follow the path? What if we make two equivalent polygons but start at different points in the path (or go anti-clockwise instead)? Do we prefer a particular edge (the shortest one to set the normalized lengths?)

This PlacedPolygon instance might decide this on its own. It contains several bits of independent info that we need to orient and measure a polygon in space. These aren’t the things that any particular polygon knows. Every instance thinks they are the center of the universe because they have no concept of anything else. If we don’t like how PlacedPolygon does it, we simply make a different class that does what we want (without disturbing the polygon class).

But, do you see the other thing happening? Do you recognize this yet? The polygon is the data, and the PlacedPolygon is using that data with other data to do something. The only thing left is to render it. Still guessing? How about Model-View-Controller? You might be surprised by that because today people talk about MVC as huge application-level ideas. However, that’s not how Trygve Reenskaug thought about it when he used that idea in Smalltalk. Each little thing would have their own set of MVC components and they’d send messages to each other. Imagine every widget in your webpage being its own MVC and sending messages to other widgets, each of which had their own MVCs.

Also, consider this is how many image manipulation programs work. They associate the original image with a set of transformations. You always have the original. And, this is the path to undo/repeat: you can have queues of transformations that you apply, skip, whatever, but still always get back to the original object.

Wrapping it up

Where do the façile examples go wrong? The examples show inheritance because they are demonstrating a feature. They aren’t trying to demonstrate good design. It’s a big problem when anyone is trying to come up with tractable and relatable examples that can fit easily on a page.

- The instances know more than they should and do things unrelated to their identity.

- Inheritance interferes with reuse. The Square / Rectangle problem is a problem because people give Rectangles responsibilities they shouldn’t have.

- We’re told a square is a type of rectangle somewhere in grammar school, but what we’re really being taught it that two things share a particular set of properties. It’s easier to manage that in software by comparing properties rather than hard-coding these relationships.

- People tend to shove everything they know about something into the class that represents it. Consider the Employee class examples!

I presented an alternative, but as I equivocated many times, you don’t want to design past the point where you get any additional flexibility or benefit. What I’ve implemented might not be the right approach for your problem, but you should still go through the process. What does an instance really know about itself, how can you compartmentalize it and protect it from the application, and what other ways do you have to manipulate it?

Some other things to read

As is my bad habit, I start writing these things before I do any research. Sometimes I convince myself that doing that allows me to work out the ideas without bias, but really I’m likely polluting the internet with stuff that other people have already said.

I was pleasantly surprised how unoriginal I was, though. That is, we’re exposed to a lot of ideas because they are in (bad) books and in (bad) presentations, but we often don’t see the counterargument. There are very good, very thoughtful programmers and designers out there who don’t write books or make presentations, so we don’t often hear the other side of the story. For example, some of these thoughtful discussions were only motivated by someone asking a question, unlike this post where I’ve just been annoyed by this for a long time and needed to get it out of my system.