Neil deGrasse Tyson obscures the truth, again

Neil deGrasse Tyson, whom I’ve previously shown to repeatedly distort the truth about van Gogh’s Starry Night, makes some very basic mistakes in astrophysics, in which he holds a Ph.D., while on Hot Ones. It’s not a new mistake for him either, but it suits his political goals.

The host, Sean Evans, is famous for his deep research to find obscure topics from his guests’ past. But this softball setup is not something obscure about Tyson:

Sean Evans: So now that you’ve eaten ten scorching hot chicken wings on YouTube with a bald guy I think this is now as good a time as any talk about how insignificant we all are.

Tyson likes to push a particular philosophy that eliminates the things he can’t explain, doesn’t understand, or finds inconvenient. His response somehow turns anti-humanist:

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Yeah we have come to define significance as I’m special, everything else isn’t. Religions thinking they’re special, cultures thinking they’re special, individuals thinking they’re special.

Then he makes his science mistake, and it’s not just saying “atoms” when he means “elements”. His mistake jumped out to me because I spent quite a bit of time in graduate school thinking about element production in the universe. But a high school student interested in the same thing would know this. Or, maybe, the host of the “Unafraid of the Dark” Cosmos:

The top four ingredients in life in your body top 4 atoms in order hydrogen oxygen carbon nitrogen those four atoms do you don’t the top ingredients are in the universe the top four chemically active atoms in the universe hydrogen oxygen carbon nitrogen.

And then his logic mistake where he goes from that to a conclusion with no support:

I am the universe yes so upon learning that you’re not special because you do not contain special ingredients

Tyson is expressing a political opinion and bending the science to support it. It’s no secret that Neil deGrasse Tyson thinks he’s special and treats people poorly. Part of that game is that he has to make sure that other people don’t feel special, and he does that by shitting on them. Tyson is all about punching down.

##

Carl Sagan, an actual extraterrestial posing as a human and the host of the original Cosmos, contrasts the world-annoyed, pedantic Tyson in his first words of the first episode:

The Cosmos is all that is or ever was or ever will be. Our feeblest contemplations of the Cosmos stir us—there is a tingling in the spine, a catch in the voice, a faint sensation, as if a distant memory, of falling from a height. We know we are approaching the greatest of mysteries.

Shortly after those lush poetic sentences, he adds even more wonder. We are not just boring space matter:

Some part of our being knows this is where we came from. We long to return. And we can. Because the cosmos is also within us. We’re made of star-stuff. We are a way for the cosmos to know itself.

And give credit where credit is due: Ann Druyan, who eventually married Sagan, co-wrote, produced, and directed this amazingly presentation of our knowledge of the skies. She also wrote the movie Contact, where Jody Foster acts out Sagan’s words “The universe is a pretty big place. If it’s just us, seems like an awful waste of space.”

In another video, he’s just as inviting:

Our ancestors worshiped the Sun and they were far from foolish. It makes good sense to revere the Sun and the stars because we are their children; we have witnessed the life cycles of the stars they are born they mature and then they die as time goes on. There are more white dwarfs. More neutron stars. More black holes, the remains of the stars accumulate as the eons pass. But interstellar space also becomes progressively enriched in heavy elements out of which form new generations of stars and planets life and intelligence. The events in one star can influence a world halfway across the galaxy and a billion years in the future.

and also:

All the elements of the Earth except hydrogen and some helium have been cooked by a kind of stellar alchemy billions of years ago in stars, some of which are today inconspicuous white dwarfs on the other side of the Milky Way Galaxy. The nitrogen in our DNA, the calcium in our teeth, the iron in our blood, the carbon in our apple pies were made in the interiors of collapsing stars. We are made of starstuff.

First, the Drake Equation

If we aren’t special, why aren’t there more of us out there in the Universe?

The Drake Equation is a bar napkin estimate of how much intelligent life might be out there. It takes the probability of stars with planets, the probability that those planets are in the right orbit to support life, and so on, to estimate how close extraterrestrials might be and if they might communicate with us. Each estimate is a fraction, so the total probability gets very low quite fast.

We haven’t found any aliens.

But Tyson thinks that they may be avoiding us:

I wonder if, in fact, we have been observed by aliens and upon close examination of human conduct and human behavior they have concluded that there is no sign of intelligent life on Earth

This is a weird stance to take. It’s based on the idea that we are too stupid, but at the same time, that we are the most interesting thing going on in this planet. It’s utterly tragic that Tyson misses what fiction writers have said on the subject.

In JRE #1658, Joe Rogan calls out Tyson for his lack of curiosity after he says:

Now think of the hubris of us saying this advanced civilization of aliens who can cross the gaps of space are interested in us and our gonads and they want to paint circles in our crops that’s kind of weird. I don’t think we’re that interesting.

Joe Rogan understands the pull of science more than Tyson:

That’s why I had that argument with Neil deGrasse Tyson about it. Like, why would they care about us? … We go study slugs you know we study spores and microbes. Why wouldn’t they study territorial apes with thermonuclear weapons?

He goes on to say that we’d lose our human minds if we found a frog on Mars. Just a frog.

But work it out for yourself. If we’re stupid, that works out for colonizing aliens. It even works out for scientist aliens. Or colonizing scientist aliens:

Or, the aliens might come to eliminate us as the problem since we are not the interesting thing on this planet:

This is a pretty important point: if we are not special, who cares, besides us, if we “destroy” the planet. Earth is going to be just fine, with or without us. The planet doesn’t care if we wreck the atmosphere so it cannot support life, whether by losing ozone, being too hot, whatever. The plants die, the animals die, and we all die. The planet doesn’t care. The planet will still be here and will just start over. We’d be a mere blip in the planet’s history. If it were an episode of Friends, it might be “The One With Humans”, just like there might be “The One with Dinosaurs” and “The One with Trees”.

What really dies is our human conception of earth, of Gaia, of Mother Nature. And, if we aren’t special, as Neil deGrasse Tyson says, and aliens would not care what we think,

Elements are rare, and so are atoms

Tyson says the human body is mostly four different elements (although he says “atoms”, which is not quite right, but whatever). Humans are mostly Hydrogen, Oxygen, Carbon, and Nitrogen. Those are indeed the top elements in our bodies. He jumps to the conclusion that we are not special since those are most common elements in the Universe.

This isn’t a light point, because his Ph.D. thesis was on elemental abundances of the center of the galaxy.

But, in his claims, he doesn’t let on that the baryonic matter (i.e., atomic matter), is a small sliver of the Universe. NASA says that the Universe is about 73% dark energy, 23% dark matter, and the rest, about 4%, is all the stuff we have ever seen (baryonic matter). Those numbers are slightly fuzzy and experiments divide most of the Universe slightly differently, but the baryonic fraction is always around 4-5%.

We aren’t even made from the most common stuff of the Universe. This is something that Tyson surely knows; he does have a Ph.D. in Astrophysics and he hosted a TV show on the subject. But, he’s not trying to educate us on Science, so facts and context are not important.

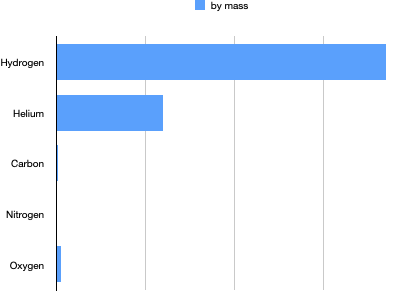

In that 4-5% of the mass of the universe, the four most abundant elements by mass are, in order, Hydrogen, Helium, Oxygen, and Carbon. Tyson omitted Helium on purpose because it’s inconvenient for his point. That’s why he has to add “chemically active”, since Helium is a noble gas and as such, chemically inert. Once he knocks out Helium, he can promote Nitrogen, the fifth most common element, into fourth place. But, Nitrogen is exceedingly rare in the Universe. It’s a stepping stone to Oxygen in solar production of the light elements.

Here’s a bar plot of their relative mass fraction. Hydrogen is about 74% of the baryonic mass, Hydrogen is about 24%, Oxygen is about 1%, and then you can barely notice that anything else is there. Looking at this chart, the egregious omission of Helium is more apparent:

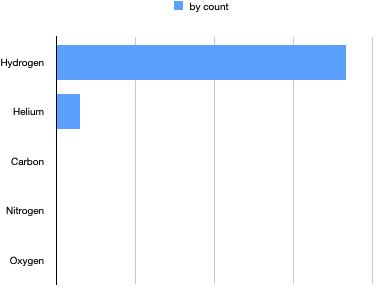

This looks even worse if you count atoms instead of weighing them. Since Carbon is about 12 times heavier than Hydrogen and Oxygen is about 16 times heavier, their fraction by mass gets a big boost. By count, they virtually disappear:

We are not made of the main elements of the Universe. We are made of the most abundant one, Hydrogen, and then some minor ones. That looks even worse when we look at our bodies composition.

And, remember that all of this is just 4-5% of the Universe. That Oxygen bar that you can barely see is relative to just the baryonic count.

There might not be any dark matter

Let’s say that there is no dark matter, which is something astrophysicists invented to explain why the galaxies didn’t rotate the way we expected them too. And, I think we should use the original name: dunkle Materie. We’ve never been able to see this, so it’s like Einstein’s cosmological constant. It’s fairy dust.

There’s another theory that doesn’t require dark matter fairy dust to explain what’s going on: Modified Newton Dynamics. This article isn’t about that though.

Even if I concede that there is no dark matter, there’s another major point that doesn’t depend on baryonic scarcity.

Oxygen is rare

Oxygen is rare in the Universe and it’s rare in our solar system. Mercury might have water ice in its polar craters, and Venus has an atmosphere of carbon dioxide. Some of Jupiter’s and Saturn’s moons have Oxygen in their atmospheres, but those are barely atmospheres at all. Oxygen is just 1% of 5% of the Universe, so of course it’s not everywhere. What’s really interesting is that it becomes concentrated anywhere.

In 1998, NASA launched the Submillimeter Wave Astronomy Satellite to look for two oxygen spectral lines, a water spectral line, a carbon monoxide line, and a carbon line. They hoped to find Oxygen in interstellar clouds. They did not find it. The 2001 Odin project also failed to find it. Oxygen is rare in the Universe. And, many of these experiments are looking specifically for elemental (neutral) Oxygen.

By mass, Carbon is half as plentiful as Oxygen, while Nitrogen is a tenth as plentiful. That they are ranked a couple places from Hydrogen doesn’t make them plentiful. It’s a bit of misdirection to explain anything by simple ranking. For extra fun, read about Zipf’s Law.

Hans Bethe, one of the giants of Physics, was awarded the 1967 Nobel Prize for his 1939 paper, “Energy Production in Stars” in Physical Review. It’s a paper I had photocopied and kept in the binder of papers I read often. It set out how stars started with Hydrogen to make Helium, then Lithium, Beryllium, Carbon and so on.

Our Sun is a main sequence star that’s mostly making Helium out of four Hydrogens in the “PP chain”. Slightly bigger stars with higher pressures and higher temperatures make Oxygen in several steps by fusing Hydrogens to isotopes of Carbon and Nitrogen in the “CNO cycle”.

Curiously, Bethe thought that the CNO cycle, which would make Oxygen, was the major energy producer in our Sun; it’s not. Our Sun is not making Oxygen in any appreciable amount because our Sun is just a tad too small to have the pressure and temperature required for that.

Other stars are making Oxygen, and that stellar Oxygen sits inside those stars until they runs out of fuel and can no longer fight gravitational collapse. When the star has to relent to the weakest fundamental force, the stars collapse on themselves then explode, sending their contents out into space as the dust that make nebulas. When you look at Orion’s Belt and see his sword hanging down, know that the middle bright thing a cloud of dust left over from an exploded star.

That dust can then accrete again to make new stars, perhaps with heavier-element dust from other exploded stars. The cycle starts again. Eventually you get stars large enough to make Oxygen. And yet, for all the billions of years the Universe has existed, we’ve only worked our way up to 1% Oxygen in baryonic mass.

Our bodies, ourselves

Tyson listed the four elements in order of decreasing mass fraction, while skipping Helium. By mass in the Universe, it’s Hydrogen, Oxygen, Carbon, and Nitrogen. It’s mostly Hydrogen, and trace amounts of everything else.

In our bodies it’s a bit different. We’re about 65-70% water, and water is two parts Hydrogen and 16 parts Oxygen by mass. Every water molecule gives Oxygen an eightfold advantage by mass, and there’s a hell of a lot of water in us.

Our bodies are only about 10% Hydrogen, by mass. The most abundant element is barely in our body at all relative to its appearance in the Universe. It’s 74% of the baryonic matter, but only 10% of us. It’s not even the second most abundant element in our body. Carbon is about half as abundant in the Universe as Oxygen, but it’s twice as abundant as Hydrogen in our bodies.

Tyson the punter

Our body’s composition argues against Tyson’s point that we are not special. If we were the same mass fractions as the universe, he might have a point, but we have inverted the proportions. We have specifically excluded Hydrogen as the most important element and built ourselves around an element that’s 1% of 5% of the Universe.

All of this happens against the Second Law of Thermodynamics. We have specifically decreased local entropy by organizing rare elements far beyond their natural abundances. This doesn’t even consider that we can’t do without heavier elements such as Phosphorous, Potassium, and Sodium. If we don’t have those, our bodies don’t work. That’s the entire point of Gatorade.

Here’s Carl Sagan again, in Episode 4 of Cosmos.

I’m a collection of organic molecules called Carl Sagan. You’re a collection of almost identical molecules with a different collective label. But is that all? Is there nothing in here but molecules? Some people find that idea somehow demeaning to human dignity, but for myself, I find it elevating and exhilarating to discover that we live in a universe which permits the evolution of molecular machines as intricate and subtle as we. The essence of life is not so much the atoms and small molecules that go into us, as the way, the ordering, those molecules are put together.

The entropy angle itself should be interesting to a scientist. This leads to exploring the composition of asteroids and meteors, the planets that formed from those asteroids and meteors, how we got liquid water onto this planet, and so on.

Tyson forecloses all of these questions, though, because we’re nothing special to him. There’s nothing to wonder about and no interesting questions to ask. A scientist is the person who wonders “How did it get this way?”. Tyson is actively arguing against that wonder.

If aliens showed up, and he’s often said he hopes aliens exist, would they be special? If they are, why aren’t we? And if they aren’t, is nothing special?

But, Tyson is also anti-philosophy, seemingly from a mistaken, utilitarianist perspective. He simply thinks it’s a waste of time because it doesn’t “advance” science. But, he’s always seemed to be a backward, Victorian-era thinker to me; less scientist and more cataloger and collector. He doesn’t need to think about what he is doing because it’s just work. That Philosophy doesn’t get through Science’s to-do list is its chief failing to him. And, remember, he’s a Doctor of Philosophy.

But the philosopher might quip that Philosophy doesn’t score touchdowns, and neither does Science. I think that might be lost on Tyson, but who better than a philosopher to think about what “special” or “advanced” means, their relationship to what we are doing, and what we should do about it?

Just the numbers

To summarize, here’s the rundown of just how rare we are, elementally:

- The universe is Dark energy (73%), Dark matter (23%), and Baryonic matter (4%)

- Helium, which is not in out bodies, is 24% of that baryonic 4%.

- Hydrogen is about 73% of that baryonic 4%.

- Oxygen is about 1% of that baryonic 4%, or 0.04% of the matter in the Universe.

- That 0.04% of the Universe makes up about 65-70% of our body by mass.

That Oxygen would get together to do that seems very unlikely, and we don’t have any proof that it has happened anywhere else. Still, that’s not special enough for Tyson. Worse than that, he doesn’t think it should be special to you.

Maybe we need a different role models for scientists, perhaps ones with a bit more gumption. They don’t even have to be real. Or maybe we just need to abandon Tyson on Mars.

Finally

Sam Kriss might have said it best in Neil deGrasse Tyson: pedantry in space:

What he actually does is make the universe boring, tell people things that they already know, and dispel misconceptions that nobody actually holds.

And later:

‘Science’ here has very little to do with the scientific method itself; it means ontological physicalism, not believing in our Lord Jesus Christ, hating the spectrally stupid, and, more than anything, pretty pictures of nebulae and tree frogs. ‘Science’ comes to metonymically refer to the natural world, the object of science; it’s like describing a crime as ‘the police,’ or the ocean as ‘drinking.’ What ‘I Fucking Love Science’ actually means is ‘I Fucking Love Existing Conditions.’