What do you really get from IDE-driven development?

I’ve been playing with GitHub Copilot, an IDE extensions that uses GitHub’s vast knowledge of how people code to suggest what you probably meant to type next. I’m running it through Visual Studio Code, but it also runs in JetBrains and Neovim.

I’m not a fan of IDEs, but I don’t mind if other people use one. As long as your tool choice doesn’t affect mine, more power to you. Indeed, try several things over your career. I even tried emacs for a year, and now I never have to use it again. But, a year is a fair evaluation period. It’s enough that I have to commit to learning it and get over the hump of initial transition pains.

But that’s not why I’m not a fan. Again, I’m not really against them, but I don’t think they help you as much as you think they do.

Awhile ago, a friend recounted to me a story about him and his team taking a class to learn a new language. Most of the team used an IDE and mostly came up with the same solutions to exercises. He didn’t use an IDE. He didn’t get method name suggestions, code completion, and so on, so his solutions were completely different. And, they were smaller and faster.

He’s a really good programmer, but that’s not why his solutions were better. Since he didn’t have suggestions to guide him, he read the docs and by simply perusing them, was aware of methods and other features that the IDE did not suggest. There were better ways that weren’t apparent in the IDE. And that makes sense: in the interface for a suggestion in an editor, how much complexity can you really manage?

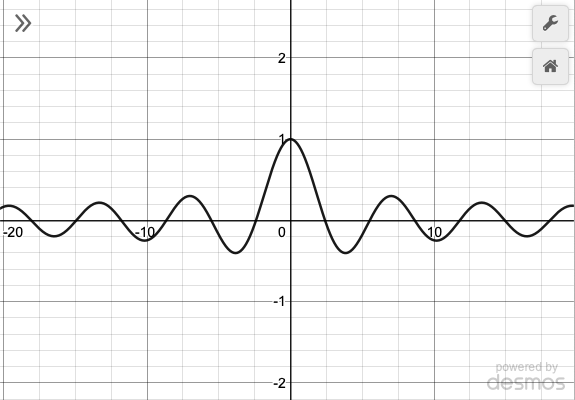

There’s an idea in math known as the local minimum. In some function, you may be in a position where moving in any direction makes you go uphill. Here’s a plot of a Bessel Function from Desmos.com, which has many local minima and two absolute minima:

If you send up around x around -17, you’ll find a spot where going either left or right makes you go uphill. If you don’t want to go uphill, you are content to stay around that local minima. This often makes sense. How much effort, in the non-mathematical sense, are you willing to expend to discover if there is a lower minimum? Go over the hill to your left and you discover a minimum that is greater than the one you were just in. Go over the hill to the right and you find a lower minimum. But, is that new minimum an absolute minimum? Restart the process.

This happens in just about anything you can imagine, but let’s consider IDEs. You start using an IDE and it makes one particular thing particularly easy, and it makes it so easy that you don’t go looking for something even easier. You can’t spend all of your time wondering if there’s a slightly better way of doing things. At some point you have to get work done, even if it might be inefficient when you don’t account for discovery, opportunity, or switching costs.

That’s the seduction of IDEs. You get something that seems to work, and you can get a bunch of things that seem to work and cobble those together. Mark Jason Dominus has an interesting perspective on Java, which he enjoyed using: You will not produce anything really brilliant, but you will probably not produce anything too terrible either.

I enjoyed programming in Java, and being relieved of the responsibility for producing a quality product. It was pleasant to not have to worry about whether I was doing a good job, or whether I might be writing something hard to understand or to maintain. The code was ridiculously verbose, of course, but that was not my fault. It was all out of my hands.

In that world, the IDE handles the complexity, and that’s how things get so complex. The IDE doesn’t care. It doesn’t have the Smithian idea of striving to be loved and to be lovely. The IDE can know the type of your data and select the proper source for method names, then filter those based on a few characters you type.

And this is where GitHub Copilot comes in. It works inside the IDE, but it’s not making “dumb” suggestions (it is, but in a different way). It knows a lot about code that people have actually written, so it knows what’s likely to come next—not just names, but entire structures. Instead of suggesting the next word in a sentence, it’s suggesting the next paragraph.

But all of this is based on what it’s learned from all of the code that it knows about. That’s a lot of code. But, a lot of code doesn’t matter because Sturgeon’s Law informs us that 90% of the code is crud. He was talking about science fiction, but it feels true of just about anything.

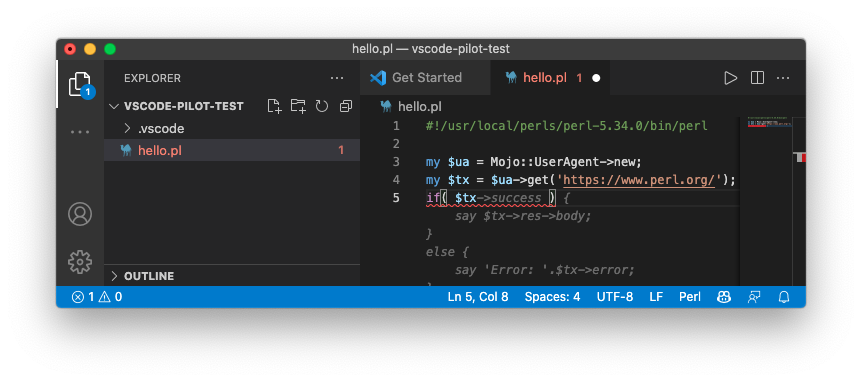

All of that code learning is parroting the bad habits of the 90% crud. I’m very impressed by the technology, but not so much by the learning sets. I tried a simple Perl example with Mojo::UserAgent (see my book, Mojo Web Clients):

I’m impressed that it suggests something close to the structure that I probably want, but not so impressed that it chose something that doesn’t work. The success method on a transaction was deprecated in 8.02 (October 2018) and removed in 9.0 (February 2021). That is, it is suggesting code that was bad three and a half years ago and hasn’t worked in a year. Garbage in, garbage out (and, there’s an interesting, unexpected history of that phrase). In that sense, the suggestions are “dumb”.

The Copilot doesn’t particularly know anything about what you are trying to do. It’s making guesses based on what other people have done. But, you aren’t doing what other people have done. You’re trying to write a good program. Well, maybe you are.

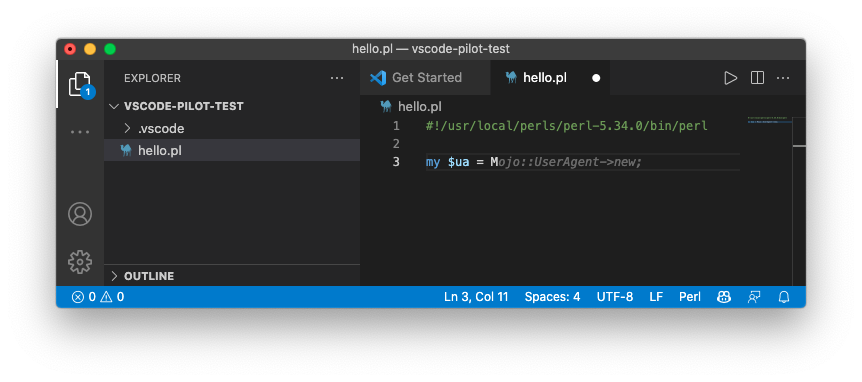

Furthermore, the Copilot knows only what you might want to type next, which is what people are used to from dumber IDEs. What does it suggest if I start typing a line that uses a module I haven’t loaded? Nothing special happens, such as suggesting a line above my typing that loads the module:

In effect, as my friend experienced in his coding class, these sorts of things don’t make better programs and don’t make us better programmers. We end up knowing less than we should and get less than we deserve.

Part of our job as programmers is to know what’s possible and what we can do. IDEs, because of their interface, aren’t about discovery. They are about typing shortcuts, and there are a limited number of things that they can show us and people who aren’t going to see the docs outside of the IDE are unlikely to look through all the options that a cramped dropdown offers them. We have yet to improve on the Smalltalk browser and we aren’t even using as something as good as that.

Typing’s a completely different problem, and one that I don’t have. I know how to touch type (yes, I’m old enough that I had a typing class on mechanical typewriters in high school). For example, Perl has the idea of synonyms. You can type out foreach, but for will do the same thing. Some people like to optimize for that. But, as an experienced typer, I don’t think of foreach as more than for. Just like we read words as units rather than sounding out its parts, I type out words as a unit rather than thinking of each character.

Even if I were a poor typer, that’s still not a significant part of my programmer time. Mostly I’m staring at a screen mapping out connections and considering consequences. An IDE doesn’t help with that. Even as I’m typing, I’m taking the time to think about the consequences of whatever I’m doing. Taking that time away means I’d create less thoughtful code.

As a postscript, I’ve heard several stories about people who leave Google or Facebook and have a hard doing being productive at the next place. Both of those companies have planetary-scaled systems and the amazing tools to handle that. The next place doesn’t have those tools, and suddenly you have to know how to do things at much lower levels. If you never learned those levels, you are practically starting over and your previous experience isn’t that important. Their tools do their things, not general things, and certainly not someone else’s things.