How much rice is that?

Someone on some podcast told the story of the chessboard and the grains of rice. Sometimes it’s wheat. Sometimes it’s some other staple, but no matter which way they tell it, the story is about exponential growth.

A lowly person provides some clever amusement for the king, who rewards with with whatever he might ask for. Appearing humble, he asks for a single grain of rice on the first square of a chessboard, two on the second, and doubled for each subsequent square. Once the king figures out the ruse, he has the person killed.

On this podcast, the person says that by the time you get to square 14, you have exceeded the entire worldwide supply of the commodity. That sounded a bit low. I don’t know what $2^{14}$ is or what it might represent, but that’s easy to figure out.

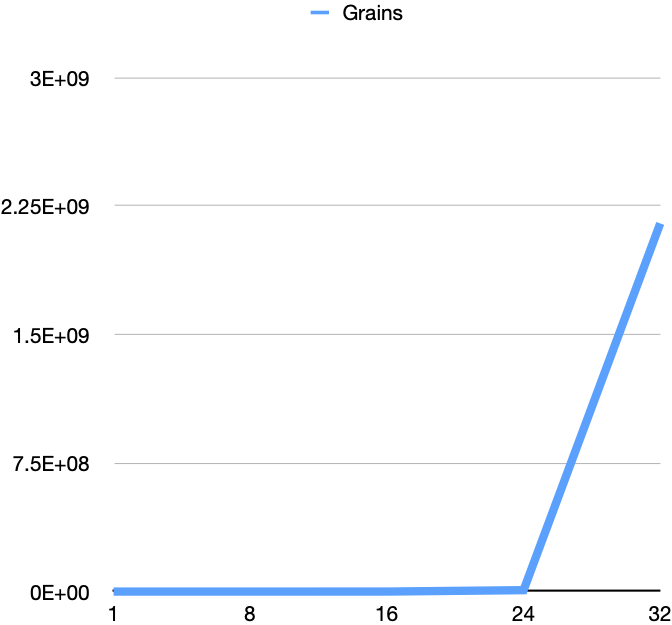

Take this plot of the grains on rice on each square. It’s nothing, then all of a sudden, something. It’s a line plot of every eight squares, giving it a more linear appearance than it deserves:

Consider the same plot but for half the board. The values on the Y axis are different, but since these are large numbers, they are as meaningless as other large numbers. It’s one, two, many.

Engineers may go for the logarithmic plot, but that’s more meaningless:

How much rice would actually fit on this chessboard? I’d never much thought about it. When you think about big numbers, forget the numbers. Relate it to something you can think about, done famously in Charles and Ray Eames’s Powers of Ten.

I knew that $2^{63}$ is a really, really big number (and, remember it’s 63 because the first square is 0 because $2^{0}$ is $1$). $2^{63}$ is about $10^{18.963}$, which is easier to think about in the physical world. It’s not as big as $10^{80}$, the number of particles in the universe and it’s not as big than $10^{27}$, the number of atoms in our bodies (maybe $10^{28}$ after the holidays). It might be close to the number of grains of sand on the Earth ($10^{21}$), where close simply means a few orders of magnitude. Those are still unfathomable numbers though.

All of which reminds me of this glib comparison:

Physicists worry about decimal points, astronomers worry about exponents, and economists are happy if they get the sign right.

Let’s get to it. How much rice is there in the world? Since rice is a commodity, there are people who track these things.

For example, the USDA tracks domestic and global production. This includes who makes how much and who they sell it to, at the country level.

So, can we figure out how much of the world’s production would show up on each square? Or, better than that, which square will be the closest to the world’s annual production?

And this is where we learn the first lesson of government statistics. They don’t report the numbers in a way that they want you to use. The domestic numbers are in thousands of cwt (centum weight, or, 100 pounds, also known as the short cwt), which is units of 100,000 pounds. The global numbers are in thousand of tonnes, which is 2,204.62 pounds (also known as the long or metric ton).

One tonne is 0.0220462 1,000 cwt, and 1,000 cwt is 45.359 tonnes.

| Year | US, 1,000 cwt | US, 1,000 tonnes |

|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 227.6 | 10,320 |

| 2020 | 243.1 | 11,030 |

With the US numbers, we can work out a global production in 1,000 tonnes. Although I’d rather report kilotonnes, that’s not how it shows up in the reports. Notice that China shows up twice. I have no idea why that is.

| Country | 1,000 cwt | 1,000 tonnes |

|---|---|---|

| China | 144,760 | |

| India | 107,246 | |

| Indonesia | 36,383 | |

| Bangladesh | 34,123 | |

| China | 27,298 | |

| Thailand | 18,196 | |

| Burma | 12,153 | |

| Philippines | 11,751 | |

| US | 243.1 | 11,030 |

| Brazil | 8,086 | |

| Japan | 7,763 | |

| TOTAL | 418,789 |

That’s the answer for that, but we can also ask Wolfram Alpha, which reports 623.8 million metric tonnes per year, or 623,800 1,000 tonnes. So, we’re pretty close.

This brings us to the second lesson of government statistics. Not only are they hard to use, but they are also wrong. Recall Stamp’s Law (from Josiah Stamp, 1st Baron Stamp recounting Harold Cox):

“The government are very keen on amassing statistics. They collect them, add them, raise them to the nth power, take the cube root and prepare wonderful diagrams. But you must never forget that every one of these figures comes in the first instance from the chowky dar (village watchman in India), who just puts down what he damn pleases.” – Harold Cox, Minister (House of Commons), 1906-1911

With the total weight of rice produced in the top 10 countries plus the US, we need to figure out how many grains of rice there are. This is a bit tricky because there are several types of rice. But, The Measure of Things estimates of 0.021 grams ($4.6 \cdot 10^{-5}$ pounds). That’s a great resource to relate numbers to physical things. That per-grain weight works out to 22,000 grains per pound, or 2.1 billion grains per 1,000 tonnes.

The annual global production is about $2 \cdot 10^{13}$ grains of rice, roughly. We can translate the grains on a square to the equivalent units of annual production. It’s not until square 45 that the amount of grain on the square is close to one year’s production. We might be able to better grasp that number by thinking about it in terms of days of production, although the rice season is very short and not year round. Recall Werner von Braun’s quip that getting nine women pregnant does not get you a baby in a month:

| Square | Grains of rice | Annual production units | Days |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.00E+00 | 5.01E-14 | |

| 8 | 1.28E+02 | 6.42E-12 | |

| 16 | 3.28E+04 | 1.64E-09 | |

| 24 | 8.39E+06 | 4.21E-07 | |

| 32 | 2.15E+09 | 1.08E-04 | |

| 40 | 5.50E+11 | 2.76E-02 | 10 |

| 45 | 1.76E+13 | 8.82E-01 | 322 |

| 46 | 3.52E+13 | 1.76E+00 | 644 |

| 47 | 7.04E+13 | 3.53E+00 | 1290 |

| 48 | 1.41E+14 | 7.06E+00 | |

| 56 | 3.60E+16 | 1.81E+03 | |

| 64 | 9.22E+18 | 4.63E+05 |

In the fable, the king kills the person once he figures out the ruse, but I think that I’d give him another option. You can have all the rice you ask, but you personally have to carry it away.

That reminded me of a story of a day trader I knew who had some future contracts on eggs. Most day traders don’t actually want the commodities; they want the arbitrage. But, he forgot about these contracts and the eggs showed up at the rail yard. He had to pay to unload and transport the eggs. That wasn’t a good day for him.